Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

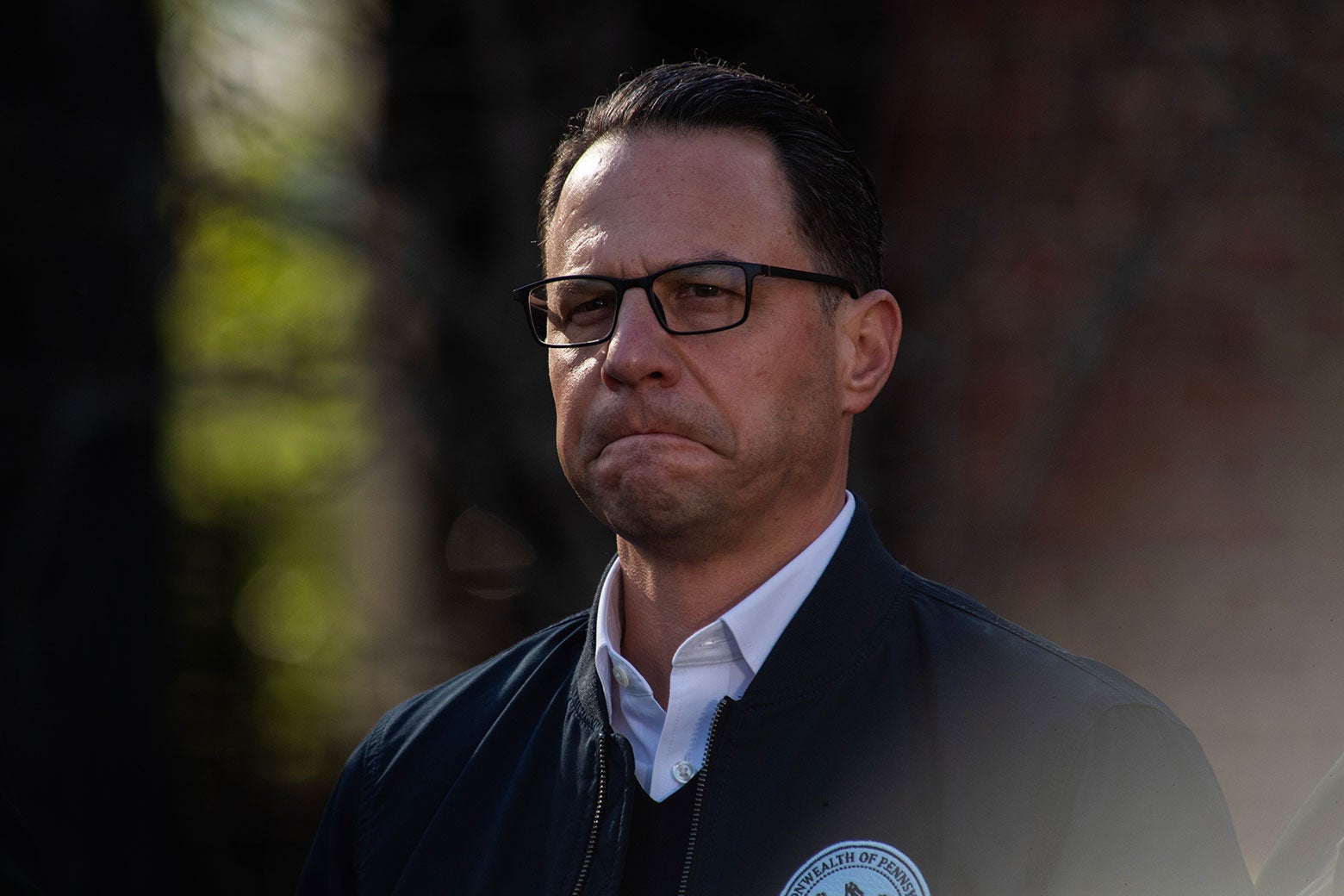

Donald Trump has survived two assassination attempts. Paul Pelosi was beaten in his own home with a hammer. Someone just tried to burn down Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro’s house while he and his family slept inside. And all of that happened in just the past year and a half alone.

But according to Kieran Doyle, the data tells a different story. Doyle is the North America research manager at ACLED, an organization dedicated to mapping and analyzing instability across the globe. Doyle tracks incidents of political violence across the U.S. and Canada. And right now, he says that despite what you’re seeing in the news, political violence is actually declining here. I asked him to explain how that’s possible, and whether this downward trend is likely to last with Trump in the White House. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Aymann Ismail: Let’s start with your finding that support for extremist partisan violence has declined. Can you walk me through how you measured that?

Kieran Doyle: We collect data about incidents of political violence and protests in the United States. We gather that data weekly from thousands of local news publications across the country, as well as from experts and the online presence of extremist groups.

One of our key findings was that despite the prevailing sense that 2024 had a high potential for violence and hyperpolarization, activity from organized extremist groups was significantly lower in 2024 than in 2020 or 2021, and we’ve seen a steady year-over-year decline in their activity since then.

Were you surprised by that result? Do you look at violence at protests?

I didn’t think our findings were surprising because we’d been seeing this trend for a while—especially in terms of extremist group activity. Just to clarify, “extremist partisan violence” isn’t a specific category we use. We track organized groups like the Proud Boys, white nationalist groups, or militia-style groups, and political violence more broadly. Street fighting during demonstrations is definitely something we track. It’s their primary form of violence. Per the number of events they attend, the Proud Boys have one of the highest rates of violence of any group. When they show up at a demonstration, they’re more likely than almost any other group to be involved in violence. That was especially true in 2020, during the Black Lives Matter protests and their counterorganizing.

There are a number of explanations for the decline, but the biggest is the law enforcement crackdown after Jan. 6 and the dismantling of many key groups. Because of that, we may be in a new political paradigm. Many leaders and participants have been prosecuted, and we’re still seeing how the landscape around extremism is shifting under the new Trump administration.

When I came to your report, I was already thinking about recent high-profile acts of political violence—like the two Trump assassination attempts and, more recently, the arson attack on Gov. Shapiro’s home while he was inside. How do you reconcile your data with what feels like a rise in particularly consequential political violence?

The assassination attempts on Trump were hugely significant politically, but they didn’t clearly map onto the current climate of hyperpolarization I mentioned earlier. After the news broke, politicians quickly assumed the shooter was some kind of activist leftist acting against Trump. But the most obvious explanation didn’t match the attacker’s actual motives—and to this day, it’s still unclear what drove him. That reflects a broader trend we’ve seen in the last few years: Many high-profile acts of political violence are carried out by individuals whose ideologies don’t align neatly with the broader political environment.

In the case of the individual who targeted Gov. Shapiro, it’s unclear whether the attack was motivated by Shapiro’s support for Israel, antisemitism, or a mix of factors. There’s political murkiness in that case too. It’s similar to how we talk about mass shootings in the U.S.—sometimes they’re carried out by people with defined political beliefs, but often the story is more complicated. I think it’s useful to think of these acts similarly: violence carried out by individuals with complex motivations.

We also have a global tracking project focused on violence targeting local officials. In places like Germany and France, there were multiple attacks on politicians ahead of the European Parliament elections. The opposition leader in South Korea was stabbed at the start of the year. Thankfully, these kinds of political attacks remain quite rare in the U.S.

At the same time, the Trump administration has taken the extraordinary step of declaring vandalism of Teslas as domestic terrorism. How would you categorize those kinds of attacks compared to, say, the hammer attack on Paul Pelosi?

We’ve recorded dozens of Tesla vandalism incidents—whether on private cars, in lots, or at showrooms—as well as the assault on Paul Pelosi. But we analyze them differently. In the Pelosi attack, there was a clear political motive, though it was carried out by an individual, so the murkiness I mentioned earlier applies—his mental health history and belief in conspiracy theories are part of the picture.

Tesla vandalism, on the other hand, connects to a broader political movement. There are mass protests against Elon Musk and DOGE happening nationwide, and this wave of property destruction is happening alongside that. There’s also a copycat effect—like what we’ve seen with mass shootings. The man who set fire to Gov. Shapiro’s home referenced the Pelosi attack and said he would’ve assaulted Shapiro with a hammer. That’s a deeply concerning connection, especially considering how hard mass shooting violence has been to curb. There’s a lot of overlap with the political violence we’re seeing from individuals now.

Given that Trump has floated sending American-born citizens to Salvadoran prisons and frequently undermines the courts, do you think violence could trend back up?

That’s a question I’d never confidently say no to. Even in the most stable moments, it’s important to remain vigilant. As I mentioned, the biggest factor in the decline was the post–Jan. 6 crackdown and the dismantling of groups most active in 2020—like the Proud Boys. That enforcement is a major reason we’ve seen less extremist violence lately.

Another factor is demonstration trends. Extremist groups tend to be opportunistic and often organize in response to larger movements. After Roe v. Wade was overturned, for example, many showed up at pro-abortion protests. The same happened during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, which saw high levels of countermobilized violence.

But for more than a year—until the Trump administration came in—the main protest movement in the U.S. was around Palestine and Gaza. That’s a harder space for these groups to engage with. Many are seen as anti-Muslim, antisemitic, anti-Israel, or anti-Palestine—so there may not have been an ideologically “comfortable” way in.

That’s one concern now with protests against Elon Musk and Tesla. We’ve seen some low-level countermobilizing already—like after the pro-Palestine protest at the Cybertruck event. The same could happen with demonstrations around Trump’s immigration policies, which are spaces where many of these groups would feel more ideologically aligned. Those are flashpoints we’re watching closely.

Right now, we’re in a moment of high political and economic volatility. That doesn’t necessarily mean more political violence—but it certainly doesn’t create a stable environment. And it makes things harder to predict, especially with lone actors. So yes, I do think we’re in a more volatile moment than we’ve seen in the past few years.

Do you hope this research shapes public discourse? Are there particular misconceptions you’re hoping to correct?

The goal of our research is to make the data available and as accurate as possible so we can better understand patterns of protest and violence. My focus is on the U.S. and Canada, but ACLED is a global project. We’re not collecting data to push a narrative—many people, like journalists and academics, use it to ask questions we’re not even thinking about. What our data shows—maybe contrary to public perception—is that extremist group activity has declined, and that trend hasn’t reversed in 2025. Compared to 2020 and 2021, mobilization and political violence are down by nearly any metric. Whether that continues is impossible to say, but it might surprise some people to learn.